Tanabata Star Festival, Fashion 1945 - 2020, Eau de Ki

Tanabata, literal translation "Evening of the seventh" on July 7th, also known as the Star Festival Hoshi matsuri, is a Japanese festival celebrating the meeting of the gods Orihime and Hikoboshi.

According to legend, the Milky Way separates these lovers, and they are allowed to meet only once a year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. The date of Tanabata varies by region of the country, but the first festivities begin on 7 July. The celebrations are held at various days between July and August.

Orihime (Weaving Princess), daughter of the Tentei (Sky King, or the universe itself), wove beautiful clothes by the bank of the Amanogawa (天 の 川, Milky Way, the Kanji literally means, "heavenly river"). Her father loved the cloth that she wove and so she worked very hard every day to weave it. However, Orihime was sad that because of her hard work she could never meet and fall in love with anyone. Concerned about his daughter, Tentei arranged for her to meet Hikoboshi (Cowman / Cowherd Star, or literally Boy Star, also referred to as Kengyū) who lived and worked on the other side of the Amanogawa. When the two met, they fell instantly in love with each other and married shortly thereafter. However, once married, Orihime would no longer weave cloth for Tentei and Hikoboshi allowed his cows to stray all over Heaven. In anger, Tentei separated the two lovers across the Amanogawa and forbade them to meet. Orihime became despondent at the loss of her husband and asked her father to let them meet again. Tentei was moved by his daughter's tears and allowed the two to meet on the 7th day of the 7th month if she worked hard and finished her weaving. The first time they tried to meet, however, they found that they could not cross the river because there was no bridge. Orihime cried so much that a flock of magpies came and promised to make a bridge with their wings so that she could cross the river. It is said that if it rains on Tanabata, the magpies cannot come because of the rise of the river and the two lovers must wait until another year to meet. The rain of this day is called "The tears of Orihime and Hikoboshi".

Incidentally, Tanabata is celebrated during rainy-season so the chances of rain are very high.

At this time, the custom was to use dew left on taro leaves to create the ink used to write wishes. These days, writing your wish on a tanzaku (small pieces of colored paper) and hanging it on a bamboo stalk on the evening of July 7 is one part of celebrating Tanabata. As the date approaches, long, narrow strips of colorful paper tanzaku, vibrant ornaments, and other decorations are hung from bamboo branches, enlivening the decor of homes as well as brightening shopping arcades, train stations, and other public spaces. Before they are hung, tanzaku are inscribed with a wish.

Bamboo is thought to have become a part of the tanabata tradition for its propensity to grow straight and tall, with upward stretching branches bearing wishes to heaven on the wind. The plant was also believed to ward off insects and was displayed to protect rice crops and symbolize hopes of a bountiful harvest. It was also believed that deities could come down and drive away evil spirits.

The traditional food of the star festival is sōmen. The long, thin noodles evolved from a woven sweet known as sakubei, whose intertwined strands were thought to resemble both the Milky Way and the weaving threads worked by Orihime. Sōmen is commonly enjoyed in a light dipping sauce. Many parents will amuse their children by topping noodles with star-shaped slices of boiled okra.

It’s a day were it’s popular to wear colorful Yukata’s and enjoy the festival.

Fashion in Japan 1945-2020 at National Art Center Tokyo

The World’s First Major Exhibition of Postwar Japanese Fashion from Monpe Work Pants to the Kawaii Phenomenon!

Japanese fashion designers began gaining worldwide acclaim in the 1970s. Until now, Japanese fashion has been discussed as if it suddenly came out of nowhere with the emergence of these designers, but this is not the case. After Japan began modernizing, dressmaking and tailoring were introduced in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) and became widely popular after World War II, and Japan developed its own unique sartorial culture.

This exhibition follows the unique trajectory of Japanese clothing, especially in post-World War Ⅱ Japan, as seen from both sides: that of designers who transmit culture by creating clothes and ideas, and that of users who receive it by wearing the clothes and at times create era-defining grassroots fashion movements. It offers a comprehensive overview that references the predominant media of each era, such as newspapers, magazines, and advertisements.

Prologue: 1920s - 1945 From Traditional Japanese Clothing to Modern Dressmaking

In the Meiji Era, Western-style dressmaking and tailoring were introduced as part of a national modernization policy. While people gradually adopted the new clothing, they did not abandon traditional Japanese attracts. In the 1920s, however, “modern girls” (young women dressed in Western styles and leading relatively liberated lifestyles) appeared in increasingly hyper-consumerist urban areas, and glamorous images of them were splashed across various media.

During World War II the entire population was mobilized for the war effort, and de facto civilian uniforms called kokumin-fuku (lit. “national attract”) were designated as appropriate dress for a wide range of situations, from everyday activities to formal occasions. As fighting intensified, almost all men came to wear kokumin-fuku. Several varieties of “standard attract” for women were also decreed, but in practice, the most widely worn women's garments were work pants known as monpe.

1945 - 1950s: The Postwar Heyday of Dressmaking

During the immediate postwar era when goods were scarce, women relied on kimono they had in their homes and a limited supply of other fabrics, which they reworked into new outfits or monpe work pants. Soon there was a rush to enroll in vocational schools and acquire dressmaking and tailoring skills. Women who attended dressmaking schools referenced magazines, “style books” and other publications, and arranged clothing designs as they liked. The dressmaking craze that spread nationwide played a decisive role in popularizing Western-style clothing in Japan. In the late 1950s, the heyday of Japanese cinema produced fashion trends derived from films, such as scarves wrapped around the head, called Machiko-maki after a movie character, and the beach styles of the taiyo-zoku (lit. “sun tribe” ).

1960s: From “Making” to “Buying” Clothes

A long period of robust economic growth expanded the middle class and boosted consumption in Japan. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics helped spur a growing number of households to buy color televisions, and TV began to eclipse the movies in terms of cultural influence. As mass production of high-quality ready-to-wear clothing became feasible, the clothing consumption paradigm gradually shifted from tailoring to purchasing. The global youth culture that had emerged in London, UK spread to Japan, and miniskirts and heavy eye makeup became popular. Among young men the look known as “Ivy,” modeled on that of American university students, was prevalent.

1970s: The Rise of Individualistic Japanese Designers

Young Japanese designers emerged who were internationally active, presenting their collections overseas and gaining increasing prominence. In Tokyo, a group of the most cutting-edge designers formed TD6 (Tokyo Designer Six), and diverse new trends such as ethnic-inspired “folklore” and the concept of unisex clothing reflected individuals' varied lifestyles. On the streets, student protests and the counterculture intensified in the late 1960s, and T-shirts and jeans became extremely popular as a symbol of democratic attracts. Harajuku became a capital of youth culture, and the establishment of magazines such as An-an played a key role in heightening interest in fashion.

1980s: The Golden Age of “DC Brands”

In the 1980s, when Japan's economic growth reached its peak, the phrase kansei no jidai (“era of sensitivity”) appeared frequently in media discourse. This zeitgeist was exemplified by large numbers of people dressed in so-called DC (“designers and characters”) brands, which emphasized designers' originality and vision. On the other hand, sportswear and scanty “body-conscious” silhouettes were also popular. The diversification of style continued with the emergence of brands that sought to offer high quality at low prices. Thirty-two Japanese brands participated in the landmark 1985 “Tokyo Collection,” and the Japanese fashion world became even more vibrant.

1990s: New Styles from Shibuya and Harajuku

After the economic bubble burst, new trends increasingly came from “the street.” Young people led the way in developing and popularizing Ura-Harajuku (“backstreet Harajuku”) fashions from the popular stores lining the narrow lane nicknamed Cat Street; the high-school girl culture centered on Shibuya; and Shibuya-kei, which revolved around a specific music scene. In the late 1990s, soon before the Internet came to dominate popular culture, numerous magazines targeted at highly specific groups, such as those specializing in snapshots of idiosyncratic street fashions or directed at kogal (girls with heavily tanned skin, dyed hair and gaudy clothing) . Stylishly dressed readers were featured in magazines, and became influential fashion leaders themselves.

2010s: Toward a “Nice” Age

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant Accident occurred on March 11, 2011. Business conditions declined further, and efforts were made to realize a sustainable society as a means of reducing the burden on the environment and the economy. The period also saw the advent of the kurashi-kei lifestyle, which stressed a careful way of living, and “normcore,” which favored an exceedingly simple form of dress. Fast fashion became more prominent, and relaxed and casual styles emerged as the mainstream. Personal communications using the Internet became standard practice, and the influence of cities as centers of information transmission waned. And weeping era-defining trends gave way to a wide range of micro-trends, each with its own set of devotees.

Fashions of the Future

Today, the popularity of social media across a wide range of generations has reduced the distance between urban and rural areas as well as Japan and the rest of the world, enabling anyone to transmit and receive information at will. And as clothing can also easily be purchased on the Internet, the cycle of consumption has accelerated. Today, it is difficult to imagine any form of manufacturing that is not sustainable. Then, in 2020, we were confronted with an unprecedented crisis as a pandemic, COVID-19 (novel coronavirus), spread across the world. As restrictions against going outdoors were issued, many of the problems that plagued society in the past, including environmental pollution, and ethnic and sexual discrimination, rose to the fore, and designers also began to reexamine the function and potential of fashion under such circumstances.

Eau de Ki

Eau de Ki, icon of the house for more than 90 years, draws its origins in the family company Sankodo. Founded in 1926, the Japanese house had designed a mysterious and original water called "Medicinal Opal Water". This water met with immense success when it was offered to the general public. Perceived as Miraculous Water, “Medicinal Opal Water” was constantly revisited and improved by the following generations who religiously pass on its know-how and its secrets.

Very attentive to the quality of the products, the new generation of Sankodo has developed an innovative fermentation technique which increases the effectiveness of the elixir; Ki was born water. Today, the elixir has been raised to the rank of a mythical product in Japan.

Eau de Ki brings together in precious water two fundamental and necessary elements for life in Japan: vital energy and water.

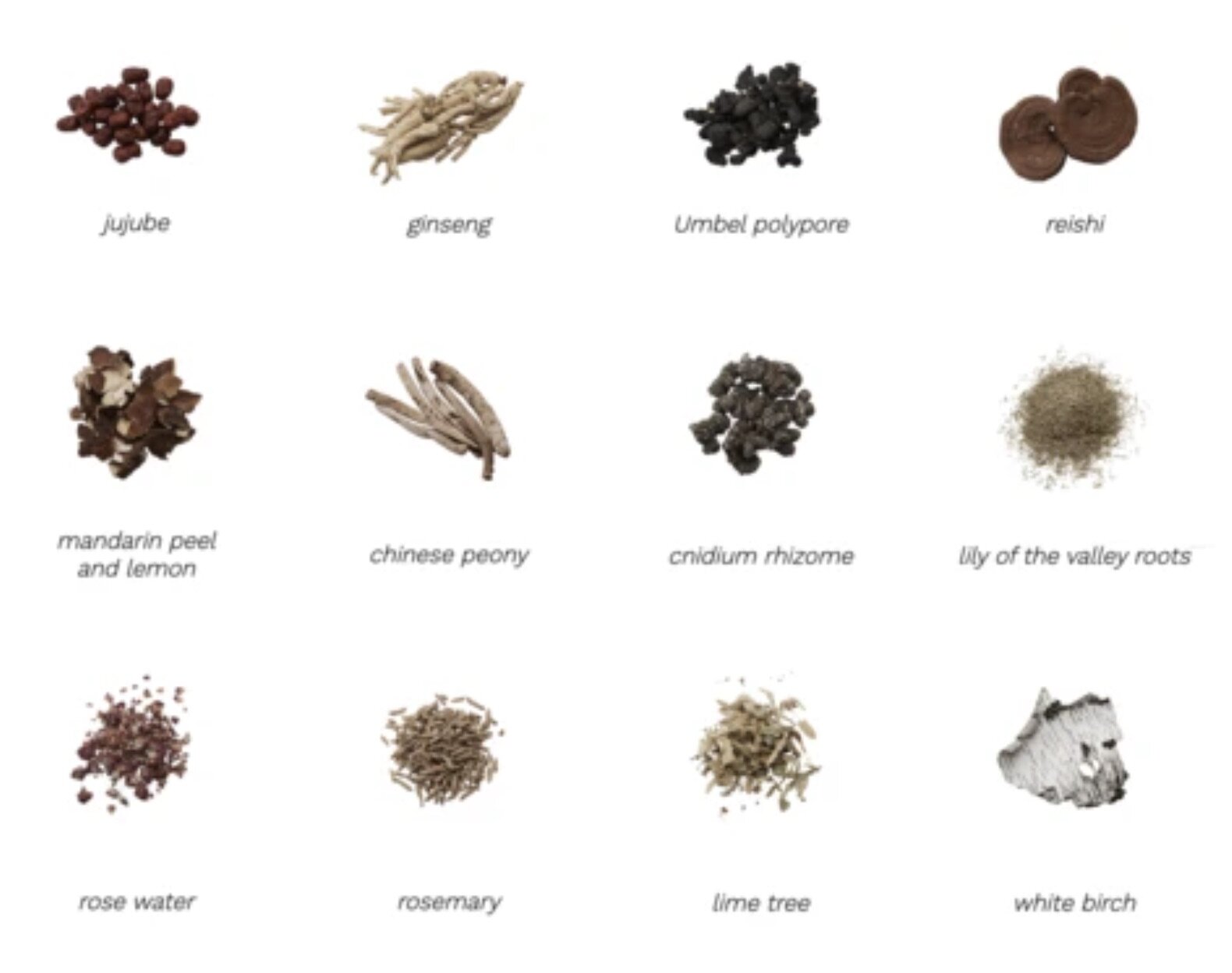

For almost a century, the elixir has been prepared with a unique making process: 8 Asian medicinal plants and 4 Western aromatic plants (jujube, ginseng, umbrella polypore, reishi, lily of the valley roots, cnidium rhizome, Chinese peony, tangerine zest) and 4 western aromatic plants (rose water, rosemary, white birch and lime blossom) are infused during six months in large earthen jars according to a traditional Japanese method.

Thus, like quality spirits, Eau de Ki has no expiration date, the quality of the lotion increases over time.

Thanks to this nectar, Ki Water allows the skin to repair itself naturally, thanks to its own strength, and restore youth and radiance.

To purchase this product please visit Bows & Arrows or visit our online store Here!